The Other Crumb

In which I rewatch Terry Zwigoff’s acclaimed 1994 documentary on controversial comic book artist Robert Crumb. (Or is it?)

I am not a fan of Robert Crumb or his work. While his talent is clear, and I can easily respect the man’s dedication to his craft, his art, in both thematic and aesthetic terms, does little for me.

But this statement should (I hope) hold little weight for those who get something out of Crumb’s work, and many do. You see, comic books were never my thing.

It might then seem odd that I would not only choose to watch but—some ten-plus years later—rewatch a two-hour documentary for which he’s the subject. But that’s just it: I don’t believe he is the subject; at least for me, he isn’t.

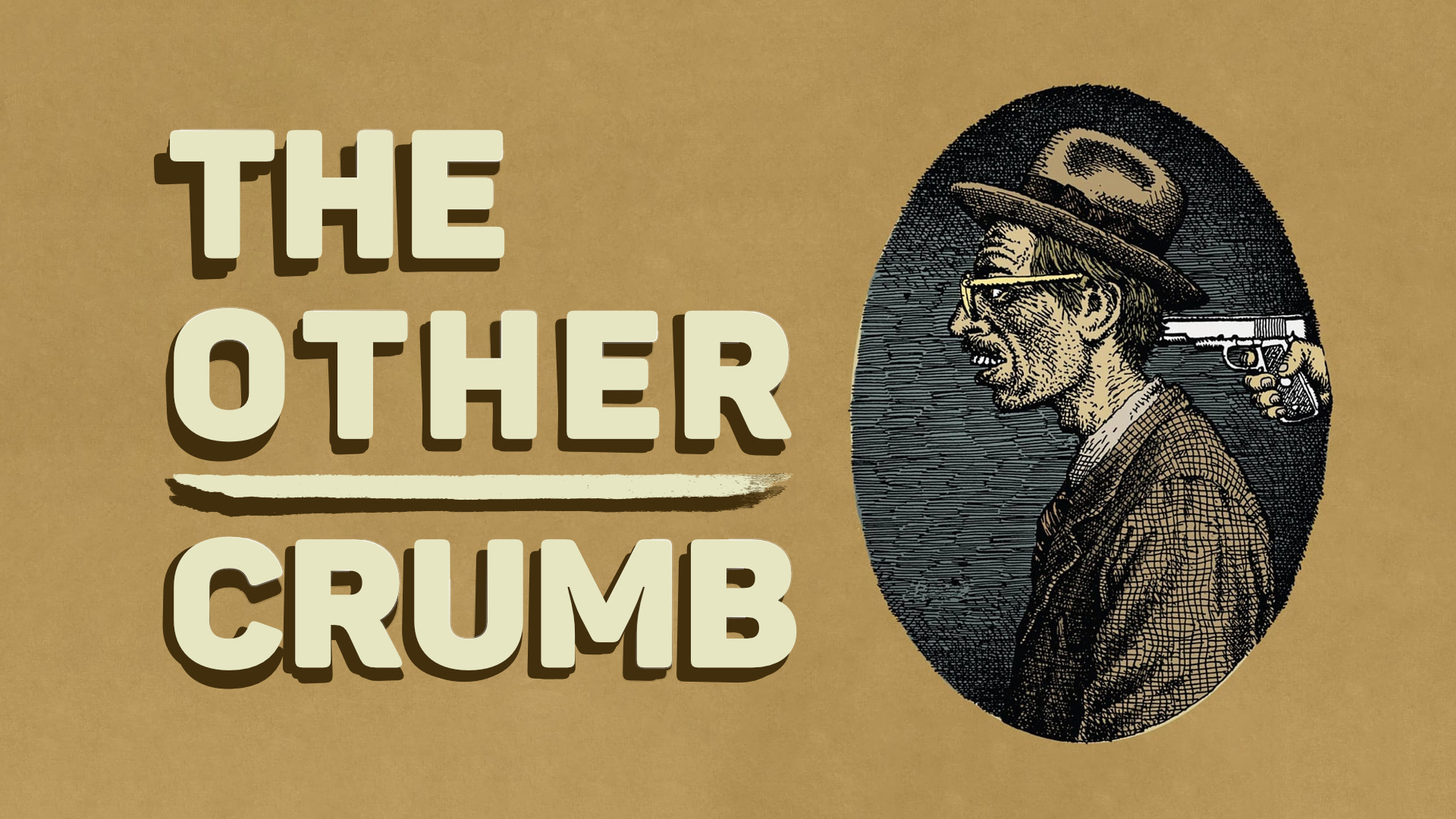

Crumb’s first words in the film are about how depressed and suicidal he becomes when he doesn’t get to draw. He says this, scribbling away at a self-portrait. Drawing, for him, is about exploration. He doesn’t know what it is he’s working on until it reveals itself. This particular drawing depicts him nauseous in bed, a large TV camera looming over his distressed pate; the subtext is none too subtle.

“I enjoy drawing, that’s all. It’s a deeply ingrained habit. It’s all because of my brother, Charles.”

We’re about three minutes into the film at this point. The next shot shows Crumb in a hotel in Philadelphia, his hometown, speaking to his mother on the phone about the crew possibly coming by to interview Charles. It was funny watching this back as it seemed director Terry Zwigoff was keen to quickly shift the film’s focus from the famed Crumb to his older brother in the shadows1.

Alas, his mother says Charles doesn’t want to be involved. Crumb doesn’t force the issue. He says Bye, putting down the handset, then turns to the crew and says, Well, that’s that, raising his hands in swift defeat.

Thankfully, for the documentary’s sake, it wasn’t.

While in Philadelphia, Crumb was asked to give a speech at an art school, which provides a glimpse of what the film might’ve been like if he were the sole figure.

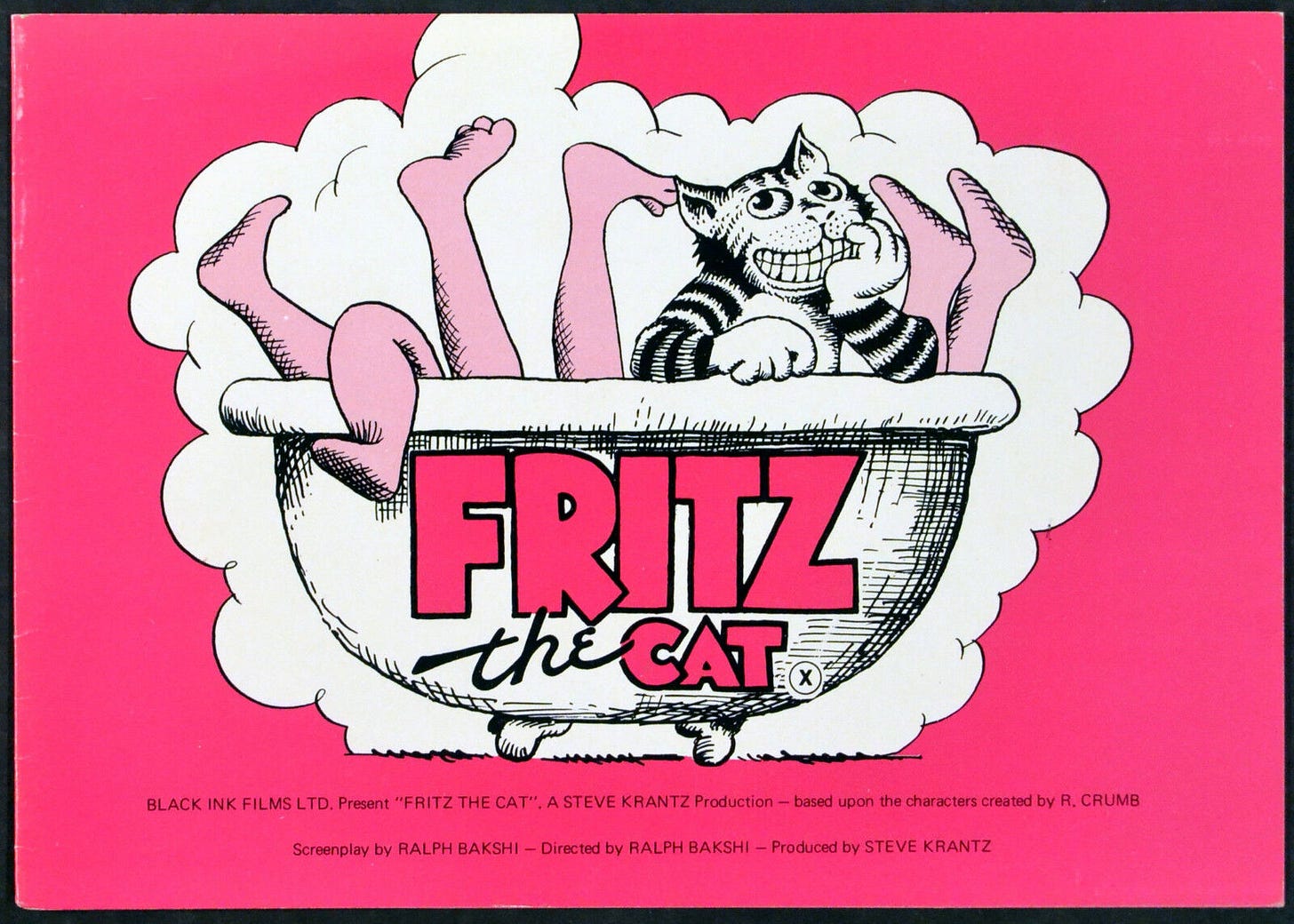

On stage, Crumb treats his young audience to a half-arsed slideshow of his work. When he speaks, it’s the voice of a petulant teen, mopishly describing the acclaim his comic strips have received, how this’n’that person screwed him over and how he was so peeved by Ralph Bakshi’s animated adaptation of Fritz the Cat that he later killed off the character in spite.

Am I being too mean? Since rewatching Crumb and thinking about writing a brief review, I have seen many—including a few clips of present-day contentious figure Jordan Peterson—heralding the artist and this documentary as an instructive example of someone who escaped a fraught upbringing and managed, through dogged perseverance, to become a success not only financially, but also crucially in their relationships with the opposite sex, where, before, there was flatly zero. That is a take, for sure, but for me, it is far too simplistic and idealised; it suggests a fairy tale ending that trauma seldom allows.

Ostensibly this is what the film is about: trauma and its varying and continuing effects on three brothers. Those who have as a child experienced abuse from a grownup know only too well the shattering impact it has on their development and self-worth. Depression and mistrust of others are almost a given and tough to reconcile. It is common, also, for those abused to be drawn towards creative pursuits, whether it be painting, music, writing or similar. These outlets offer a private space within their control, and the act of creativity (of bringing something new into this world) gives meaning and validation to a life once splintered by the selfish mistreatment of an adult2.

Sandwiched between older brother Charles and younger brother Maxon, Robert Crumb appears to be the least affected by what they went through as children. Either that or his success as an artist has afforded him some footing to climb out from the wretched pit their past left them in. Again, I’m asking myself, am I being too mean about Crumb? Earlier I criticised his teenage-like demeanour—well, it’s hardly surprising that his personality is somewhat arrested in adolescence, is it? Though I find his general personality in the film irritating, I should perhaps give him some leeway there.

But just because someone’s experienced a horrible upbringing doesn’t exempt them from criticism. Crumb’s work is frequently (and blatantly) racist, sexist and juvenile, and though it has indeed brought him success, adoration and the attention of women who before would not look twice at him, there’s a hateful cynicism he has towards it and everyone in turn3.

It’s with Charles’s introduction that the documentary becomes something much more than a fluff piece for its namesake. Crumb credits Charles with getting him into drawing. Immediately we picture a young boy emulating his older brother, seeking his approval. Together they would work on home-spun comic books—many of which Crumb has kept and are intercut throughout the film, charting over time the advancement of one brother and the deterioration of the other. Even now—1994—Crumb tells the crew he still thinks of Charles when he works on his comics and whether or not he’s gonna like ‘em.

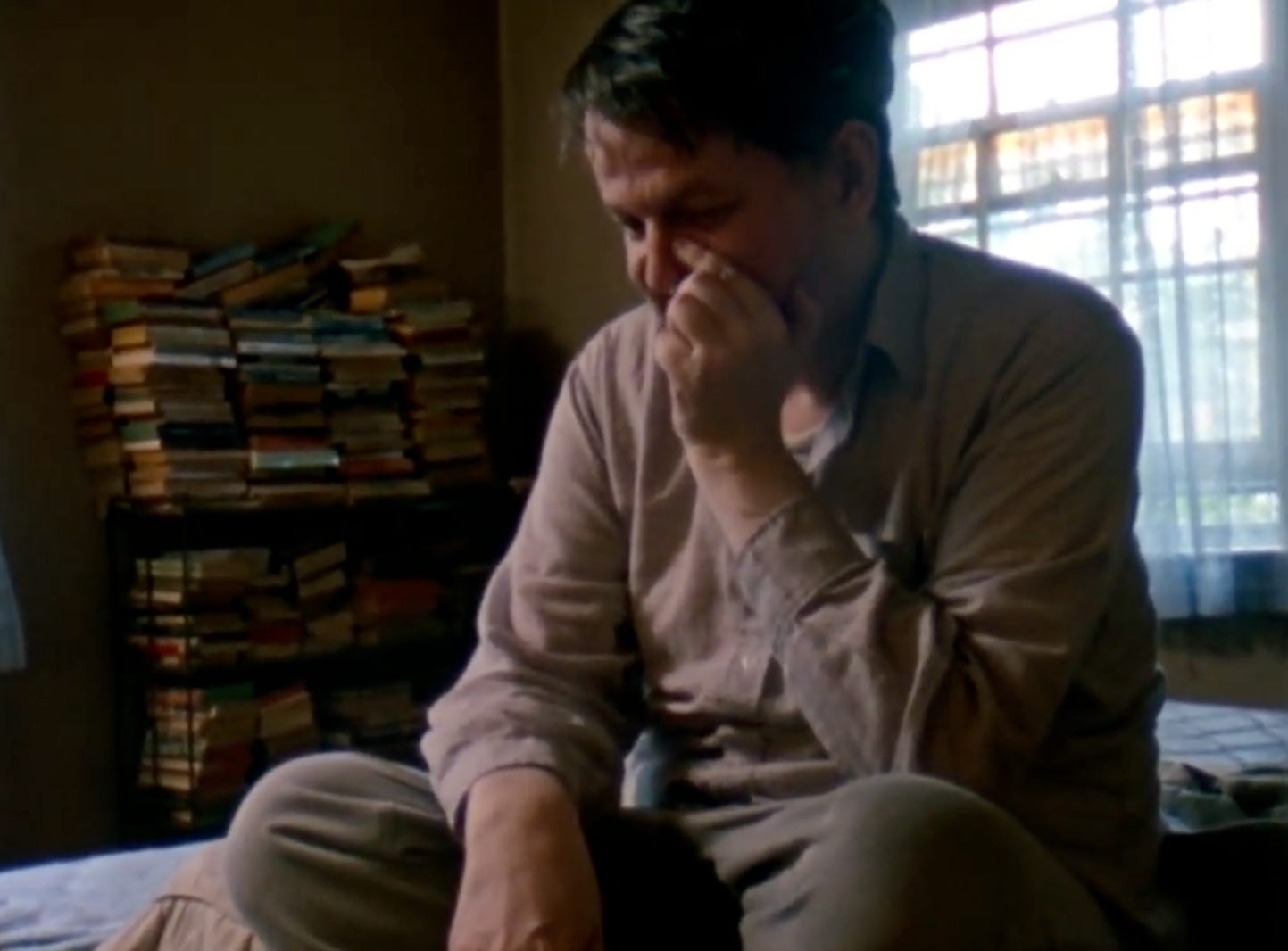

But Charles is no longer an artist. It’s not that he became something else; it’s that he has become nothing at all. We meet Charles at the home he still shares with his mother. The interview is conducted in his room, where he’s sat, legs folded at the edge of his bed, his celebrated brother on the armchair next to him. Behind Charles we see double stacks of horizontal paperbacks atop units. He has read them all and is now reading them over since there’s nothing else to do. Charles speaks in a similar cadence to his brother, but his voice is duller, more muted, due most certainly to the tranquillisers and anti-depressants he takes. From this setting, we get to know the person, Crumb’s idol and saviour, in many ways.

They were once competitive with one another. They both wanted the same things. Crumb, we gather—despite his insistence that his brother is much funnier and smarter than he is—prevailed with art, with women, and with life overall. Charles’s animosity is ever-present, softened only by the breathy chuckles that punctuate his frankest statements.

But that animosity existed long before his younger brother eclipsed him. Crumb shares a story of them as children, rooting around the trash for mislaid treasures. Charles found a beautiful toy, a wooden ice cream truck. Crumb was envious and wanted to play with it, but Charles wouldn’t let him so much as touch it. Crumb complained to his mother, who then told Charles he must share with his brother once he’s through playing. Fifteen minutes later, Charles came into the house and said, “OK, Robert, you can play with it now”, and when Crumb ran outside, he found his brother had smashed it to smithereens against the wall of the house.

Crumb tells another anecdote of the time Charles confessed to him that, when they were teenagers, he had to fight the urge not to run a butcher’s knife through his heart. Charles confirms this, adding, “Or go down in the basement and get an axe and bash your skull in with it.” He and Crumb both laugh at the remembrance. Charles, playing analyst, says that he knows where his homicidal tendencies stem: an excessive degree of narcissism. Terry asks him what the connection is between narcissism and homicidal tendencies, and Charles, quick to reply, says, “When narcissism is wounded, it wants to strike back at the person who wounded it.” Crumb turns to his brother and asks if he has ever wounded his narcissism. “Many, many times,” Charles replies, saying it twice. Crumb laughs, a big guffaw.

We learn much more about Charles, who he was and is now in 94. We learn that he once was considered handsome—there was just something wrong with his personality. Sex was all he thought about in his late teens and early twenties. Crumb later tells the crew that his brother has never been with a woman. Now, Charles says, his sexual desires are completely dead. He speaks frankly about the masturbation habits of his youth and how now he can no longer achieve an erection, which he attributes to the medication, a lack of external stimulation (for he seldom leaves his home), and ageing. We learn about Charles’s multiple suicide attempts and that it’s because of these that he was put on medication. He once drank a bottle of furniture polish and took an overdose of sleeping pills. “There were about two or three other attempts besides that one,” he says.

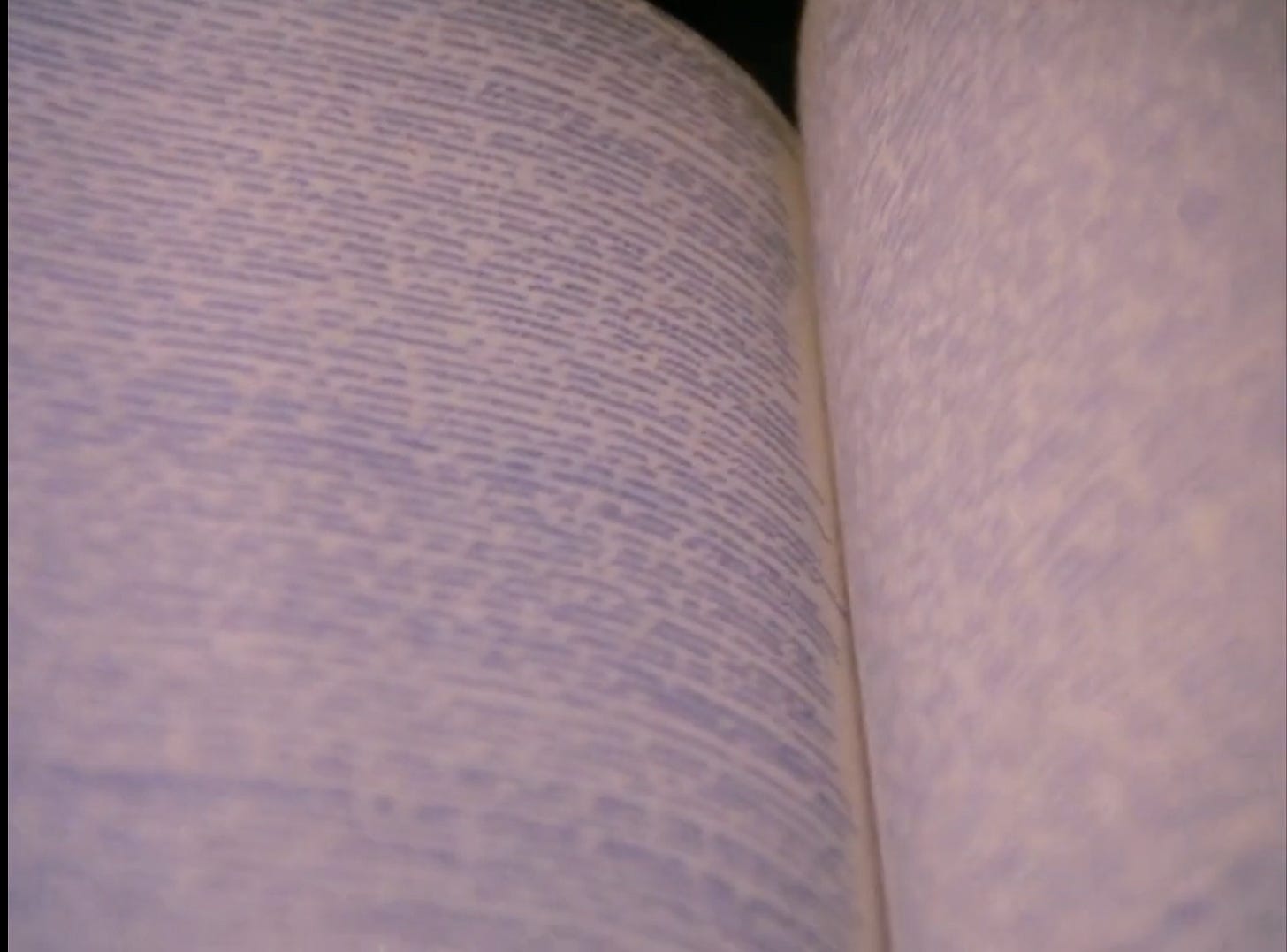

In one of the most remarkable sections of the film, Crumb pulls from his archive a whole history of Charles’s comic book work. Progressing through the years we see an almost willed (or unwilled) withdrawal from that world. It’s like seeing an artist’s mental unravelling rendered pictorially. First to manifest is a new obsession with lines, odd wrinkles that cover his characters’ clothing and later their faces, often running discordant to the rest of the styles in the zine. Then, his text bubbles grow and grow, taking up more room in each panel, and the illustrations shrink, relegated to thin slivers before being squeezed out entirely. The panels eventually become text-only, and soon after, the text becomes non-sensical. Next, Crumb pulls out notebooks that Charles filled out, where he has moved away from actual words with meaning to a dense scribe resembling words. It’s quite the metaphor. Entire books are filled end-to-end in this minute scrawl. It suggests the habit—the compulsion—was still there, but whatever message or story Charles once wanted to convey was now missing.

Crumb is an incredible documentary. There is simply too much to unpack, so I suggest watching it if this review has piqued your interest. (It’s now available through Criterion.) I didn’t even get onto Maxon, Crumb’s younger brother, who is an enigma in his own right. Maxon is mostly seen barefoot, sitting in the lotus, compulsively fidgeting with a bullet. At one point, he pulls out a homemade nail bed and describes his process of using it. “It gratifies your intestines,” he says.

In fact I wondered, rather churlishly, if the crew had been filming Crumb for a while and grew tired of his puerile attitude (as it is appears in this film).

But I watched this part over a third time with Terry Zwigoff’s commentary track, and apparently, he and Crumb were best friends long before. It turns out the whole notion of this documentary arose when Terry, during a trip to Philadelphia, stayed with Crumb at his mother’s house and met Charles.

Zwigoff even goes on to say he wouldn’t have made the film without Charles.

The film doesn’t go into great depth about this. Their father beat them “unmercifully”, especially Charles, who says (of himself) he had a, “subconscious desire to be punished.” He calls his father a “sadistic bully”, and laughs, but it is of course far from funny. Crumb says, one Christmas when he was five, his father broke his collarbone while beating him. Between their father, their mother who “was an amphetamine addict” and the ostracism from the other kids at school (especially girls), the cumulative affects were “devastating”.

Though married, throughout the film Crumb is seen constantly ogling and touching other woman and climbing onto their backs. He insists he has never been in love. There’s a resentment towards women when he speaks. They like him because he’s famous, not for his looks or personality, which suggests that he uses them for his wants as they use him for their edification.

This is reflected all through his work. One comic, Bitchin’ Bod’, depicts the perfect woman (seemingly in Crumb’s view): one without a head; an object to fondle, fuck and pass around.

In later years, Crumb has spoken about these past works (the racist ones too) and has said he was playing around with stereotypes and those who were offended often misunderstood his intentions. (He never really believed those things.) He appears much more erudite in his older years, which gives his words some credence—either that or he’s a wizened man more aptly justifying the prejudices of his younger self. The door, as always, is open to interpretation.

I was never into comics either. I always felt like everyone else was into them except me. So I've found a new member to the 'Weren't into Comics Club' now.

What was your reason for not being into comics? I looked at them occasionally, of course, but I didn't particularly care for them. I wasn't really a fan of superheroes. Weren't big on heroes generally. Always self-righteous and square. I always preferred the villain. When I played cops and robbers, I was always bandit. I hated the weird costumes they wore. The little pants over their tights. Didn't seem right. I preferred The Hulk, although I only watched the 70s TV show. Didn't read the comic Hulk.